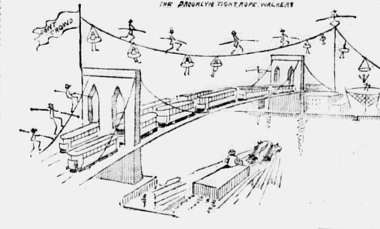

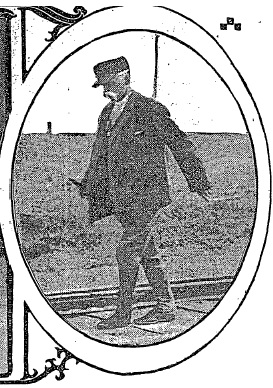

We here at Forgotten Stories are always fascinated by those moments when an idea takes root; you know, those moments that cartoons illustrate by showing a light bulb above Wiley E. Coyote’s head. Unfortunately, history doesn’t preserve how Oldrieve came up with his idea, but we do know that sometime during the summer of 1888, while working as a tightrope walker at Revere Beach in Boston, Oldrieve decided to embark on an exciting new career as an aquatic pedestrian.

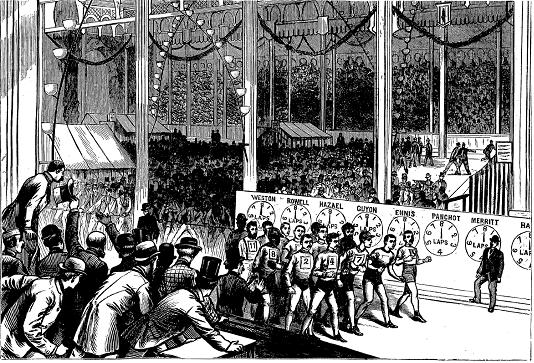

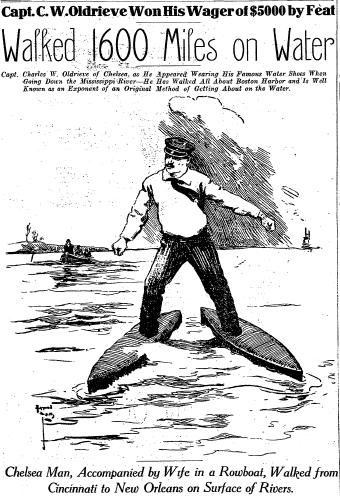

Now, pedestrianism was quite a popular sport in the 1880s and had been so since the Civil War’s end. Thousands gathered to watch pedestrians such as Charles Rowell and Edward Payson Weston compete in 500 mile walking matches in huge indoor arenas for big cash prizes. Well, if those chaps could make a good living taking a stroll on land, Oldrieve saw no reason he couldn’t figure out a way to take a stroll on the water. Taking a hint from the rowboats which pleasure-seekers took out into Boston harbor, and building on a previous water-walking attempt by a gentlemen named Ned Hanlen who’d abandoned the pursuit and gone into rowing matches instead, Oldrieve fashioned an ingenious pair of water walking shoes.

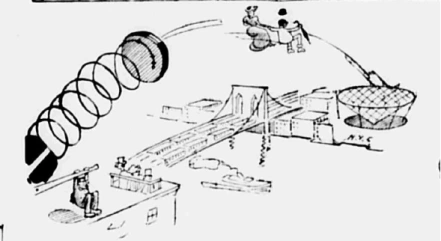

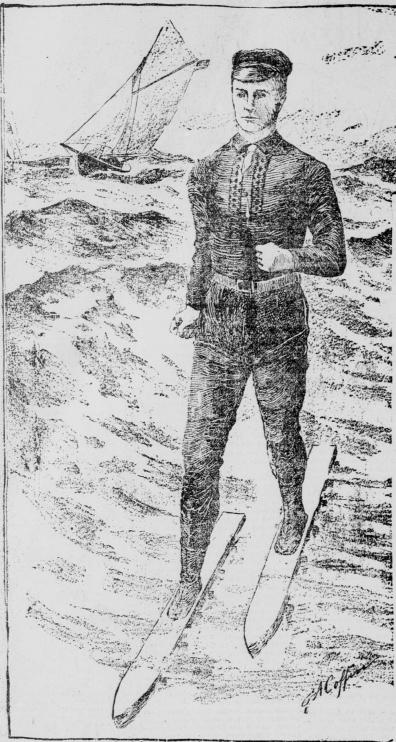

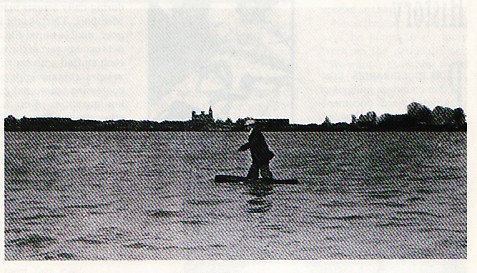

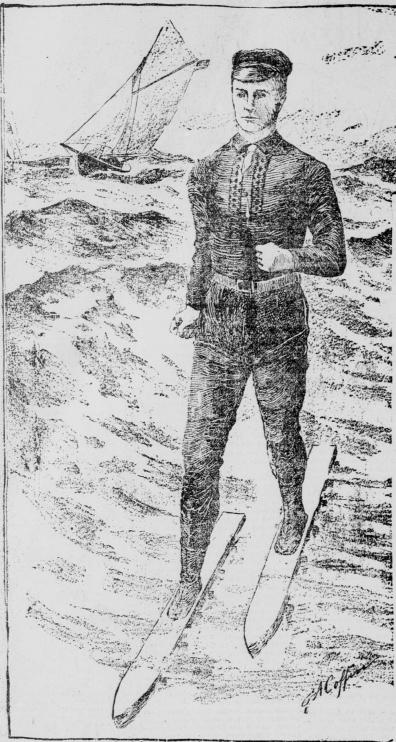

Made of cedar and copper plating, the shoes were water tight. “On the bottom of the water shoes,” wrote The Evening World, “are fins so arranged that when the foot is moved forward they lie close to the bottom of the water shoe, but when the foot is pushed back in the motion of walking they drop down and secure a hold on the water.” After a few trial walks on Boston Harbor, Oldrieve realized he had a problem; no one particularly cared whether he could walk on water, and if no one cared he certainly wasn’t going to make any money at it. Scrounging together some $500, Oldrieve became his own publicity agent by laying his funds on the line; if anyone would be willing to match his $500 he’d be willing to stroll down the Hudson River from Albany to New York over the space of seven days.

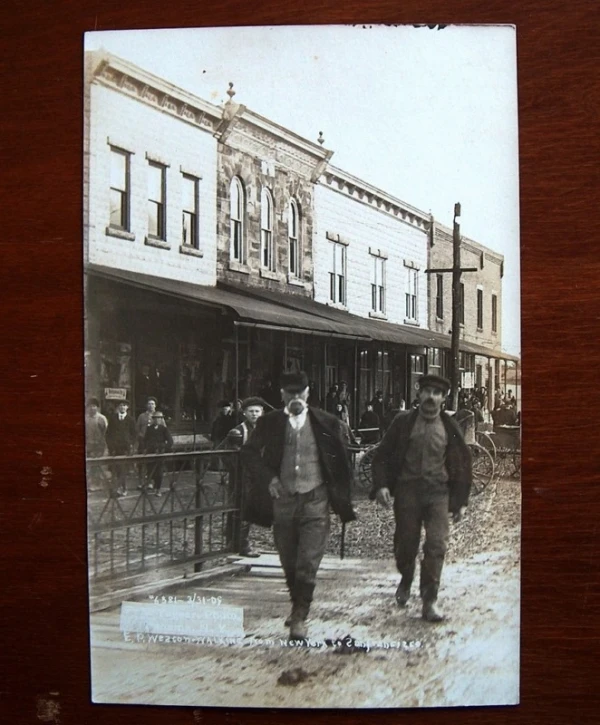

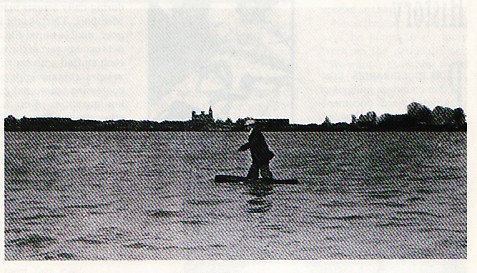

Somewhere he found a taker, and during the last week of November, 1888 Oldrieve took his stroll down the Hudson. He made it too, coming in with sixteen hours to spare. The next few days were spent demonstrating his shoes by strolling between Brooklyn and New York, and Oldrieve went back to Boston richer by some $500.00.

Once home, he doubled down, and spent the entire next year wagering on water feats. He strolled from Pemberton’s Hotel back to Boston netting a cool $100.00. During one wager he nearly lost his life; while attempting a 20 mile jaunt on the waters of the Atlantic a fog came up and he lost his way. He fortunately spotted Apple Island, struggled onto dry land and passed out under a haystack. When morning came, he built a raft and attempted to make it back to Boston. Currents swept him out to sea however, and had not a chance Coast Guard cutter appeared, Oldrieve would have disappeared. He walked the Niagara River above the Falls; betting his life that he could make it across before going over. During January 1889 he nearly died navigating the rapids of Massachusetts’ Merrimac River.

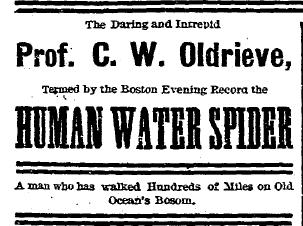

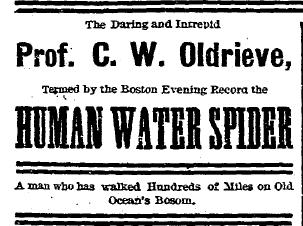

Safer pursuits were called for, and local entertainers booked him to perform off Revere Beach during the summers. Billed as “The Human Water Spider” Oldrieve strolled out onto the water with a satchel of explosives and a cigar; lighting the fuses with the cigar he dropped the explosives behind him sending forth huge plumes of water and, incidentally, stunning a few fish. He gradually built on this, bringing along fireworks to add to the aquatic display.

For the next decade or so, Oldrieve made his living performing up and down the Atlantic Coast, even going so far as Cuba. There could still be danger; as he described it in lengthy, but thrilling fashion (We trust the reader will excuse the extended quotation):

I went to Havana a few years before the Spanish War, and at the time the Cubans were struggling to thrown off the galling yoke of the mother country. My walking on the water feat proved quite a hit, and after giving several exhibitions in the bay, close to the dock, I was engaged by the Havana Yacht club for a sort of private show…the water was calm as some sylvan brook, no wind to speak of was blowing, and I felt in excellent spirits, so my performance – even if I do say it myself – was first class, and caused those dons and donnas to chorus repeated bravas from their snug resting places on the decks of the yachts.

I walked back and forth, performed a sort of gliding stunt, bent the crab, and did other foolish things, and, becoming exhilarated by my exercise, took a turn a good piece out to see…a cry of alarm sounded from the deck of the yacht nearest me. Glancing over my shoulder, I saw, just about five yards behind me, a thin, black strip showing above the water, and as it moved rapidly in my direction I quickly divined what it was, the fin of a shark. I was practically helpless, with no weapon in hand, not even so much as a paddle, and in the sudden terror that claimed me my legs grew week, with the result that I nearly lost my balance, one foot inkling to the right and the other to the left, and I came within an ace of pitching head first into the sea.

The yacht of the mayor was only a few yards from me, and, pushing forward my right foot, I sped toward the haven of refuge. But as I covered an inch my pursuing foe covered many feet, and a scream from one of the white-robed ladies on the deck apprised me that the destroyer was upon me. Instinctively, I described a turn, and facing about, saw six feet of bluish, clammy-looking flesh, a double row of pointed teeth, set well in a cavernous mouth and round, pointed beak to the side of me, as the shark sprang from the water. He missed me by a narrow margin, and his while great length – there must have been twenty feet of him – in a half circle splashed into the water, and the passage of the massive body through the flood whirled me around like a top.

As soon as I recovered myself I started again for the yacht, and had almost reached the boat’s side when the cry of alarm once more came from the deck. I could hear the swirl of the water behind me, and, looking over my shoulder again saw the same murderous fin parting the green wavelets. The shark, profiting by his first miss, did not spring from the sea until he had clearly overtaken me. His hard beak grazed the rear end of my right shoe, and caused my leg to shoot forward from under me, and as I fell backward into the sea the monster fish turned over on his side, and snap went his dreadful jaws. The bite tore away all of one portion of my left water shoe, and the calf of my leg was mangled and torn by the center teeth. As I fell into the water I felt the stinging pain in my leg and knew the shark had me in his jaws, but with a resourcefulness born of despair, I jerked my foot violently forward. My lacerated, bleeding leg was freed, as the teeth had only sunk into the loose flesh, and besides the long strips of skin I left all my left water shoe in the shark’s mouth.

I struggled about under the water for a few moments, expecting every minute to feel the shark’s teeth closing about my body, and for a time my overturned right shoe prevented me from rising to the surface. I was a good swimmer though, and when the brine had nearly choked me, by bending my right knee to the utmost, and so relieving the depressing weigh of the shoe, I thrust my head above water.

My first impression was an awful splashing all about me, and for a moment I fancied the shark and some of his family had come back to finish lunch. Spray was dashed in a deluge into my face and for a moment the water, descending in a cloud, blinded me. But then I saw it all. Several boats were floating near me, ordinary skiffs I mean, and the men in them were beating the water with the flats of oars. That’s a good ruse to frighten sharks you know and it must have worked with my hungry friend…The beating of the water was all right and no doubt saved my life, but the excitable Spaniards kept up the practice with such persistency, shouting loudly all the while that for a time I was in danger of having my brains knocked out…A boat was quickly pulled to where I fought to keep my head above water, and, more dead than alive, I was drawn over the gunwale, water shoes and all, and carried to the yacht.

I had lost much blood and a large strip of flesh was missing from my limb, and to add to my pain and misery the doctor insisted on burning the wound out with a solution of nitric acid, declaring that the shark’s teeth might have been infected from eating some dead carcass thrown into the sea.

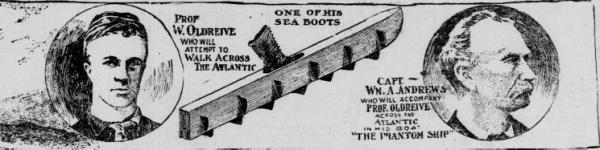

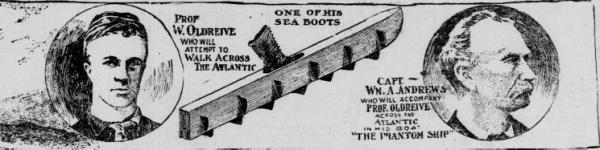

After some time on crutches Oldrieve recovered, and in the winter of 1897 announced that he’d be walking across the Atlantic from Boston to Havre, then up the Seine to Paris. The trip would begin on July 4, 1898, and a friend, C.A. Andrews would accompany him in a small canvas boat that could be folded into a 3 foot by 3 foot square and carried under the arm. According to Oldrieve, the going would be easy, since he could glide down the sides of steep ocean swells, and he could sleep and eat aboard Andrews’ tiny skiff. By July however, the Spanish-American War had broken out and the newspapers were trumpeting the dangers posed by the Spanish Navy; the trip never took place.

For the next eight years or so Oldrieve stayed quiet. There are a few accounts of performances in Boston and at various beaches around the country; some had to be cancelled when Oldrieve got too intoxicated to perform. Somewhere along the way Oldrieve also acquired a wife; a small, slight man barely 130 pounds, Oldrieve’s bride his Caroline dominated him both personally and physically, she tipped the scale at nearly 200 pounds and had a huge pair of shoulders she’d earned rowing in the waters off her native Nova Scotia.

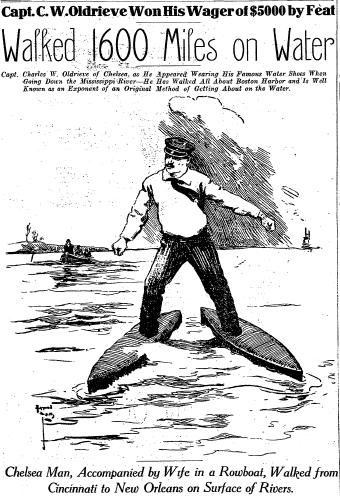

Cupid’s arrows are often wisely dispatched, and however divergent their physical natures, they got along famously. She took charge of his career, and soon she came up with a new venture. On a wager of $5000 put up by E.J. Weatherton of Dallas, Texas against the noted sporting man Alfred Woods of Boston, Massachusetts, Oldrieve announced he would walk along the river from Cincinnati to New Orleans in 40 days; taking the Ohio River until he reached Cairo, Illinois and then continuing the rest of the way on the Mississippi.

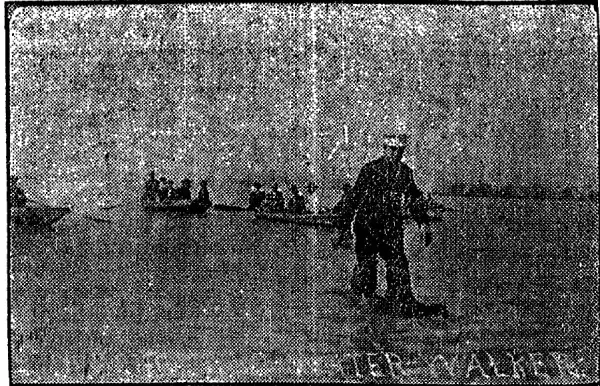

He left Cincinnati at noon January 1st, 1907. Midwest weather in early January can be particularly awful, and January of 1907 proved no exception to the rule. Although Oldrieve made around 22 miles per day along the Ohio’s waters, he was already a day behind schedule by the time he reached Paducah, Kentucky on the aftern

oon of the 14th. The wind had been particularly troubling, if it blew at his back it had a tendency to upset the water shoes, and if it blew at his front it made it particularly hard water walking. That January, the wind sometimes seemed to come at him from both directions at once.

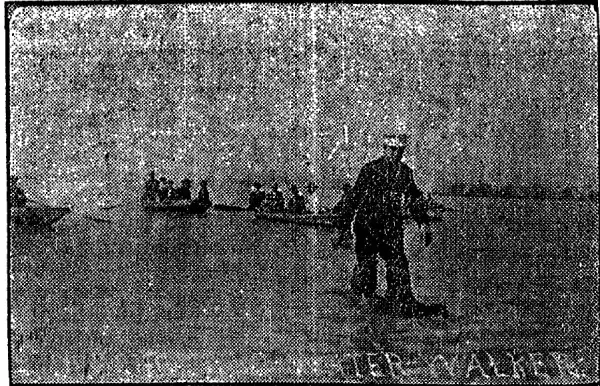

His wife rowed alongside him as he walked, shouting encouragement, providing meals, struggling to stay next to him in the strong current, and rescuing him when he occasionally fell into the ice cold water. Weatherton and Wood’s representative Edward Williams accompanied them in a gasoline launch, to verify that the Professor did indeed walk the entire way. Oldrieve assured the world that the affair would be on the level; telling the The Washington Herald, “If I win, I will win on the square.” Some good fortune hit too, he got a day’s rest when the gasoline launch failed, and was given until February 10 to finish the task.

He hit Cairo, Illinois on January 17, and a large crowd greeted him, accompanied by the whistles from passing steamboats. From here he hoped that the rapid current of the Mississippi would help him move quicker and make up for lost time. The current did help; he picked up four hours between Cairo and Memphis, arriving there on the morning of the 22nd and then continuing on towards Vicksburg which he reached on the 30th, enjoying the hospitality of Mississippi plantation owners who provided a soft bed and decent meal, gratis.

With mere hours left until noon on February 10, 1907 Oldrieve began striding past the suburbs of New Orleans, with his wife cheering him on. At an hour left, he hit the city limits, and with 45 minutes left he passed the Canal Street Bridge. Then trouble struck; Oldrieve got caught in an eddy created by a passing steamboat spinning around and around. Caroline was too far away to reach him, and as the Professor lost balance he was only just able to grab the outstretched hand of a black stevedore who’d spotted his peril and reached over the gunwale of a coal barge.

After a few minutes to recover, Oldrieve set off once more, making it to the finish line with only a few minutes to spare.

With $5000 in his pocket, some good Creole cooking, and a stay in one of New Orleans’ best hotels, Oldrieve soon recovered from his trip, and regained the 25 pounds he’d lost. He started focusing on future plans; walking across the English Channel, and even re-floating the idea of walking across the Atlantic. Meanwhile however, he and his wife gave performances up and down the Mississippi, and his water-dynamite act was to be the star attraction at Greenwood, Mississippi’s Fourth of July celebration. The Professor planned an extravaganza to cap off the event; in the foreground he would drop dynamite into the Mississippi creating giant jets of water, while Caroline set off a barrage of fireworks in the background.

Disaster struck. One of the fireworks set Caroline’s dress on fire, and instead of making for the water she jumped off the barge’s landward side in a panic. Badly burned, Oldrieve rushed her to King’s Daughters Hospital. She soon regained consciousness, and urged the worried Professor that she would be on her feet again soon. As he was unwilling to leave her side, she had to order him to take the train to Paducah to book their next engagement. He went.

Ever the trooper, Caroline’s conditions were far more serious than she let on, and in the humid Mississippi weather her wounds gave way to a rapid infection. On July 7th she died suddenly; unable to be reached by telegram, Oldrieve read about it in the paper. The hospital forwarded her body to Oldrieve, who met the casket in Memphis.

Unable to cope with his loss, Oldrieve spent the next four days after the funeral drunk, only sobering up enough to procure three bottles of chloroform from the corner drug store. Alone, in a tiny hotel room in a city where he had no friends, Oldrieve drank all three bottles. He was dead when the chambermaid found him the next morning.

Professor Shaw vented spleen at New York’s men, “Man is becoming effeminate,” he claimed. “There are now flappers in both sexes…the haberdasher sells the man lilac pajamas, embroidered bathrobes, silk slippers and cosmetics. He goes home with them, the women see them and get jealous, so they invent a new style, going the man one better.”

Professor Shaw vented spleen at New York’s men, “Man is becoming effeminate,” he claimed. “There are now flappers in both sexes…the haberdasher sells the man lilac pajamas, embroidered bathrobes, silk slippers and cosmetics. He goes home with them, the women see them and get jealous, so they invent a new style, going the man one better.” Shaw predicted a dismal future. “Women now does man’s work and gets man’s pay….Hence she is easing up on her man’s purse. That makes him ease up on his efforts. Men used to pay the car fare and the restaurant check. But girls now have their own nickels and dollars. Marriage is becoming just a way station where the train stops. It is less like the Grand Central Terminal of the old-fashioned women’s ambition.” Shaw attributed it all to the decline of the stiff collars that had rubbed men’s necks raw for 100 years, “[w]hen man changed his stiff collar and starched shirt for a soft collar and silk shirt, it was too attractive and women copied it.”

Shaw predicted a dismal future. “Women now does man’s work and gets man’s pay….Hence she is easing up on her man’s purse. That makes him ease up on his efforts. Men used to pay the car fare and the restaurant check. But girls now have their own nickels and dollars. Marriage is becoming just a way station where the train stops. It is less like the Grand Central Terminal of the old-fashioned women’s ambition.” Shaw attributed it all to the decline of the stiff collars that had rubbed men’s necks raw for 100 years, “[w]hen man changed his stiff collar and starched shirt for a soft collar and silk shirt, it was too attractive and women copied it.”