If there was one item with which New York City was oversupplied in the decades following the Civil War, it was with children. Thousands of young Gavroches left their homes in the teeming tenements, either willingly or kicked out due to lack of food. Some of them turned to robbery and pillage, forming youth gangs to loot ships in the harbor. Many young girls turned to prostitution, and those that didn’t often made a few pennies street sweeping, clearing paths through the dust and manure covered roads with small brooms so that gentlemen and ladies could walk through without soiling their clothes. Even those children who tried to get an education found the schoolhouse doors closed due to lack of room.

Where some saw crisis, the American District Telegraph Company saw opportunity. It began recruiting young boys to company headquarters at Broadway and Fourth Street, where it occupied eighty rooms on the second and third floors. The largest of these rooms was the Instruction Room, and here boys found their names replaced by numbers, and learned not reading, writing, and arithmetic, but instead were drilled by Mr. Teaguer, the Superintendent of the Instruction Room, in the District Telegraph catechism.

“Number 948, what is the greatest principle which must guide you in all your messages?”

“To find the right person in the right place”

“How would you find the right person in the right place in the business portion of the City, Number 913?”

“I would consult the nearest directory”

“How would you find the right person in a hotel?”

“By going to the office and asking the clerk on duty.”

“How in a store?

“By asking the bookkeeper or floor-walker, or some clerk who was on duty”

“How in a tenement-house?”

“By inquiring of a janitor, if there was one on the first floor; if not, I would look for the party on all the floors.”

“Number 922, what would you do in case you had to deliver stock certificates or certified checks to a certain broker or banker with whose precise business address you were unacquainted.”

“I would run as fast as I could to one of the two regular boys on the street, and ask him where to go and then as soon as he told me, I would go where I was told.”

“Where are these regular boys on the street stationed?”

“One boy is stationed at the corner of Broad Street and Exchange Place, and the other at the corner of Wall Street and Broad.”

“What is the duty of these regular boys on the street?”

“They know by being down there all the time where every banker and broker does business, and so they are able to tell all the other messengers who want to know.”

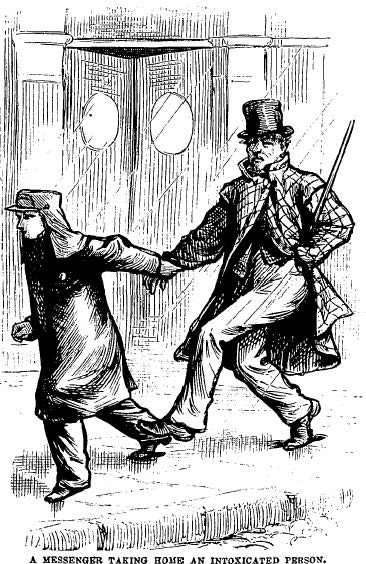

Having survived the catechism, the boys were thrust into the hurly-burly world of the District Telegraph Company’s sub-offices throughout the City, serving as two legged express agents and making $3 to $7 per week. They delivered stock certificates, checks, cash, and ran theater and opera tickets to patrons unable to make it to the box office. On afternoons where inclement weather threatened, District Telegraph boys could be seen rushing about the street delivering messages for customers unwilling to brave the cold. They delivered carpet bags to travelers at the Grand Central Depot. Thanksgiving proved to be particularly busy, and boys ran newly butchered turkeys all over town. Often, patrons hired out boys and put them in charge of more precious cargo; several of them found themselves escorting young women home from school, or watching over baby carriages while mothers shopped. Wives even sent them after inebriated husbands, and the boys walked the missing men home, for which they received a delivery receipt for “One Drunken Man.”

Having survived the catechism, the boys were thrust into the hurly-burly world of the District Telegraph Company’s sub-offices throughout the City, serving as two legged express agents and making $3 to $7 per week. They delivered stock certificates, checks, cash, and ran theater and opera tickets to patrons unable to make it to the box office. On afternoons where inclement weather threatened, District Telegraph boys could be seen rushing about the street delivering messages for customers unwilling to brave the cold. They delivered carpet bags to travelers at the Grand Central Depot. Thanksgiving proved to be particularly busy, and boys ran newly butchered turkeys all over town. Often, patrons hired out boys and put them in charge of more precious cargo; several of them found themselves escorting young women home from school, or watching over baby carriages while mothers shopped. Wives even sent them after inebriated husbands, and the boys walked the missing men home, for which they received a delivery receipt for “One Drunken Man.”

The Company expanded throughout the country, and every major city had an office. As the telephone caught on, however, the need for the American District Telegraph boys declined, and by the turn of the century the Company turned its efforts towards security services, providing guards and night watchmen for the City’s warehouses. Many of these warehouses were connected to Company headquarters via telephone and telegraph, so that in the event of burglary or fire the police or fire department could be sent to the rescue. By the 1920’s, the American District Telegraph Company started going by its initials, A.D.T., by which name it is still known today.

Check out our other great stories at forgottenstories.net.

Two of our all time favorites:

Goose Races in the Chicago River: https://forgottenstories.net/2012/08/09/come-take-a-gander-at-some-good-ol-fashioned-goose-racing/

Smash a Masher, Pt.2: https://forgottenstories.net/2012/06/12/smash-a-masher-pt-2/

![[British suffragist Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst (center) standing with policewomen Anna E. Neukon, Clara Loucks, LuLu C. Parks and Mrs. Alice Clement (left to right) inside the Hotel LaSalle].](https://forgottenstories.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/british-suffragist-mrs-emmeline-pankhurst-center-standing-with-policewomen-anna-e-neukon-clara-loucks-lulu-c-parks-and-mrs-alice-clement-left-to-right-inside-the-hotel-lasalle.jpg?w=237&h=300)